In Mexico The Past is Never Dead: The Yellow City of Izamal

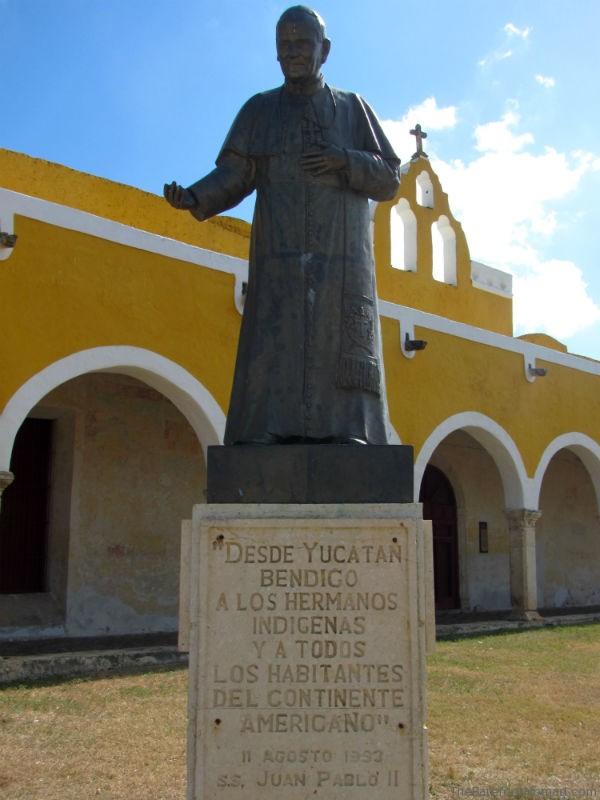

Izamal’s colonial center, painted a sunny ochre-yellow, is impressive.

In this small town in Mexico, the Franciscan convent San Antonio de Padua claims the largest atrium in the Americas (only the Vatacan is said to be larger). San Antonio de Padua was visited by the Pope in 1993, and countless numbers have walked under its archways overlooking the city plaza since it was built in 1553.

But underneath all of that history is something even older.

San Antonio de Padula itself is built upon the flattened top of the great Mayan pyramid that held the sanctuary of the god Itzam Na. The Mayans were here thousands of years before the first stone was laid on the convent.

Today’s Izamal would be but a tiny suburb of the ancient, sprawling Mayan city.

Little remains of what the Mayans built here. Bishop Fray Diego de Landa burned Izamal’s Mayan libraries and writings in the 1500s. Mayan artifacts are now scattered all over the globe, in European museums and in private collections. Remains of the Mayan world peek up through the modern town as grass-covered mounds (likely unrestored Mayan structures), reminders of so much lost and forgotten.

The Mayan structures that remain are large but less impressive than ruins like Chichen Itza or even Tulum. Kinich Kakmó, though a remarkable 656 by 591 feet (the Great Pyramid of Giza is 756 feet at its base), looks like not much more than a stepped hill today. The Mayan sites in Izamal are not reconstructed, unlike at Chitzen Iza, and few tourists visit the ruins comparatively.

So we return to the yellow city. The monastery and colonial buildings in the town are all painted a yellow that reflects the dazzling sun, which is fitting as the Mayans considered this site to be the abode of Kinichkakmo, a manifestation of the sun god.

Bells ring in San Antonio de Padua, calling worshipers to mass.

We take refuge from Kinichkakmo’s baking rays under the shade of a calesa, a horse drawn cart that still serves as an alternative mode of transportation around town. The calasas are decorated with colorful flowers, with some even sporting accessories for the horses.

The horses wait in the hot sun beside the mission. But our driver is gentle with his horse, taking the time to tell us her name (Salina), and guiding her forward with a deft flick of the reins.

On the way out of Izamal, we brave the baking heat for a peek at the back side of San Antonio de Padula. From the rear San Antonio de Padula is surprisingly large, and devoid of earthy ochre paint that marks Izamal.

Next to the mission, in the leafy plaza, vendors ply cut up fruit and ice cream, while Mayan craftsmen sell handmade hammocks and clothing, with surprisingly few of the kitschy items found anywhere tourists congregate.

A last peek inside the monastery reveals more, hidden by time. A few years ago, a worker scrubbing the mission walls discovered 16th century frescos that were whitewashed over sometime in the past, for reasons unknown. The woman in this photo may be the virgin of Izamel, but that knowledge, like so much in Izamal, is lost to time.

How to get here: Izamal is about 50 miles east of Merida, the Yucatan’s capital city. If you rent a car, it’s an easy one hour drive on well paved roads from Merida.

Fascinated by Mayan History? More Reading

A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya

Written by Linda Schele and David Freidel, who played a major role in recent efforts to interpret Mayan hieroglyphs. Detailed and a bit dry for a casual read, this is a wealth of information that rates highly on Amazon.

Yucatan Before and After the Conquest (Native American)

This is the English translation of the 1566 work “Relacion de las cosas de Yucatan,” by Bishop Diego de Landa, the friar responsible for burning many of the Mayan libraries in Izamal. This book was written after de Landa’s forced return to Spain, as a sort of self-justification for his actions in what is now Mexico. In the introduction, translator William Gates (no, not that Bill Gates), argues that this book only represents about 1% of what de Landa destroyed in his time in the Yucatan.

It’s great to see a Mayan post that isn’t about the prophecy or Chichen Itza (fascinating though both are). I very much enjoyed this one – thanks!

Julie, we were in Mexico for the end of the world, and are loving learning about Mayan culture. There are literally thousands of sites in Mexico that haven’t been excavated, and so much history and tradition that were lost.

For others interested in the layers of history in the Yucatan, another book I’d recommend is “Incidents of Travel in the Yucatan”–2 volumes written by John Lloyd Stephens in 1843 which is sort of journal of his expedition to the Yucatan in that era. He was the first to “rediscover” and document vestiges of the Mayan empire. The accompanying illustrations by Somebody Catherwood are also evocative. I admit this set might be better suited to a history geek or someone who has been to the places they discuss.

The other book which I think is an easier read is: “1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus” by Charles C. Mann. Mann covers the history of other indigenous people of North, Central and South America up to the year before Columbus’ “discovery” of the New World.There is a lot of material about the Maya.

This post (including the photos) makes me want to return to Mexico. I lived there for a year as a child in San Miguel de Allende in 1963 and just returned to that town for the first time in 2012.

Suzanne, thanks so much for the book recommendations. I’ve heard a couple of great recommendations for Incidents of Travel in Yucatan – sounds like a great book to check out.

– sounds like a great book to check out.

This is wonderful – we’ll be there next month!

Steve, I’m sure you’ll love it. We rented a car, and had a fantastic time touring around the Yucatan. There’s just so much history around every corner…

The convent looks just like buildings over here in Southern Spain! I’ve just been to places along the border of Baja California and Acapulco and Cozymel. Would love to test drive my Andalusian-tainted Spanish south of the border!!

Hi Cat,

It’s a beautiful convent. We’re planning to be in southern Spain in early spring, so I’m interested in checking out some of the architecture there!

This is the first I’ve heard of the Yellow City…thanks for the introduction!

Lovely pictures! I have ALWAYS wanted to go to Mexico; when I get the chance to do so, I will make sure to visit small towns too, including this yellow city. First to hear of it, but it definitely won’t be the last 🙂

Izamal is lovely. Another city I like very much is Valladolid, about another hour east of Izamal on the Cancun highway. A lovely little colonial city with a traditional church in each of its seven barrios. Just starting to be “discovered” by tourists and expats, but still very very Mexican.

such beautiful colors! WOW!

Built in true Spanish colonizer fashion. We regret not being able to visit this site (alongside many other parts of Mexico). Definitely coming back!

San Antonio de Padua Izamal looks majestic.

I’m glad to know about the town of San Antonio de Padua and the Mayan ruins there. We visited Mérida earlier this year, but a day trip took us west. Really want to go back to the area. Thanks for posting this to the History link-up!

And glad to see your book recommendations!